Methodology

We use a very specific set of standards that result in a consistent methodology for designing and maintaining our clients’ portfolios.

- Each portfolio is treated as a unique entity and is designed based on the specific needs and desires expressed to us by each client.

- We adjust the design of each portfolio to accommodate things like the limitations imposed by employer sponsored retirement plans or specific investments that a client wishes to continue to be held in the portfolio. In other cases clients have investments that have liquidation restrictions for certain time periods requiring us to manage withing the constraints of what is available where the investments are currently held.

- Each portfolio is then designed based on the principles described in Portfolio Selection as published in The Journal of Finance in the spring of 1952, Pareto’s Rule, and regular observation and reevaluation.

The Principles of TPWC Portfolio Design

The Personal Wealth Coach advisers use three fundamental principles to target an appropriate return and minimize the potential risk inherent in achieving any return above zero after inflation and taxes. They are Markowitz Mean Variance Optimization, Pareto’s Rule, and avoidance of non-systemic risk.

Mean Variance Optimization

In Portfolio Selection, Dr. Harry Markowitz of the University of Chicago theorized that if a portfolio was adequately diversified, risk could be defined as variance from a straight line return. He derived a formula, or algorithm, that would provide the least, or optimized variance in a portfolio at any given expected rate of return. Dr. Markowitz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1990 for his work outlined in that publication. In the works of Peter Bernstein in his book, Against the Gods, The Remarkable Story of Risk,

Markowitz’s objective in “Portfolio Selection” was to use the notion of risk to construct portfolios for investors who “consider expected return a desirable thing and variance an undesirable thing.”1.

Ideally any investment would generate a consistent total rate of return each year and never vary from that rate. In reality, once the return on a portfolio is higher than the “no-risk” return provided by long term bank certificates of deposit, the annual return varies. Dr. Markowitz observed that the higher the long term rate of return achieved, the greater was that variance. He also observed that over long periods of time asset classes had consistent behavior, unlike individual securities or even market sectors or industries.

His thesis was that by observing the relative behavior of asset classes over a long period of time in the past, one could construct a portfolio which would have the least variance at any given expected rate of return, and that relationship would hold true into the future.

An asset class is defined as a set of investments that have similar characteristics without regard to the industry or market sector of the underlying securities. For example, stocks of the largest U.S. corporations with a relatively high price-to-earnings ratio are referred to as the Large-Cap Growthasset class. The asset class consisting of stocks of large U.S. Companies with low price-to-earnings ratios is called Large-Cap Value. The same growth or value designation applies to three classes of domestic stocks, or as they are sometimes called, equities, Large-Cap, Mid-Cap, and Small-Cap. Those six asset classes constitute six of the about twenty-three that we track and have monthly data on going back over thirty-three years.

Dr. Markowitz created a discipline called mean variance optimization which has proven over the nearly sixty years since his paper was published to be by far the most consistent risk management tool available to any portfolio manager.

- Each portfolio is treated as a unique entity and is designed based on the specific needs and desires expressed to us by each client.

- We adjust the design of each portfolio to accommodate things like the limitations imposed by employer sponsored retirement plans or specific investments that a client wishes to continue to be held in the portfolio. In other cases clients have investments that have liquidation restrictions for certain time periods requiring us to manage withing the constraints of what is available where the investments are currently held.

- Each portfolio is then designed based on the principles described in Portfolio Selection as published in The Journal of Finance in the spring of 1952, Pareto’s Rule, and regular observation and reevaluation.

The Principles of TPWC Portfolio Design

The Personal Wealth Coach advisers use three fundamental principles to target an appropriate return and minimize the potential risk inherent in achieving any return above zero after inflation and taxes. They are Markowitz Mean Variance Optimization, Pareto’s Rule, and avoidance of non-systemic risk.

Mean Variance Optimization

In Portfolio Selection, Dr. Harry Markowitz of the University of Chicago theorized that if a portfolio was adequately diversified, risk could be defined as variance from a straight line return. He derived a formula, or algorithm, that would provide the least, or optimized variance in a portfolio at any given expected rate of return. Dr. Markowitz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1990 for his work outlined in that publication. In the works of Peter Bernstein in his book, Against the Gods, The Remarkable Story of Risk,

Markowitz’s objective in “Portfolio Selection” was to use the notion of risk to construct portfolios for investors who “consider expected return a desirable thing and variance an undesirable thing.”1.

Ideally any investment would generate a consistent total rate of return each year and never vary from that rate. In reality, once the return on a portfolio is higher than the “no-risk” return provided by long term bank certificates of deposit, the annual return varies. Dr. Markowitz observed that the higher the long term rate of return achieved, the greater was that variance. He also observed that over long periods of time asset classes had consistent behavior, unlike individual securities or even market sectors or industries.

His thesis was that by observing the relative behavior of asset classes over a long period of time in the past, one could construct a portfolio which would have the least variance at any given expected rate of return, and that relationship would hold true into the future.

An asset class is defined as a set of investments that have similar characteristics without regard to the industry or market sector of the underlying securities. For example, stocks of the largest U.S. corporations with a relatively high price-to-earnings ratio are referred to as the Large-Cap Growthasset class. The asset class consisting of stocks of large U.S. Companies with low price-to-earnings ratios is called Large-Cap Value. The same growth or value designation applies to three classes of domestic stocks, or as they are sometimes called, equities, Large-Cap, Mid-Cap, and Small-Cap. Those six asset classes constitute six of the about twenty-three that we track and have monthly data on going back over thirty-three years.

Dr. Markowitz created a discipline called mean variance optimization which has proven over the nearly sixty years since his paper was published to be by far the most consistent risk management tool available to any portfolio manager.

The Theoretical Efficient Frontier

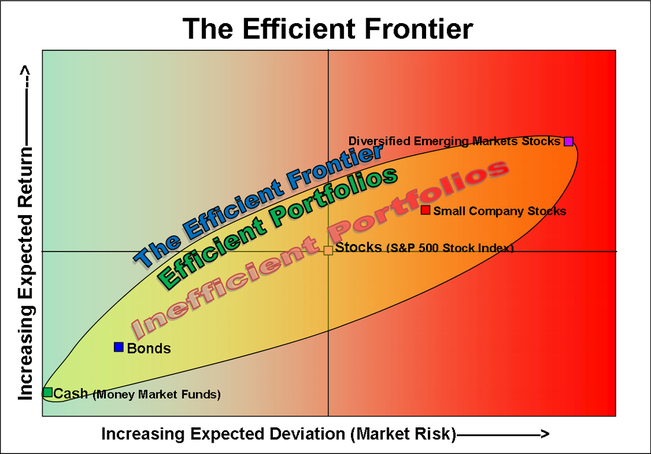

Using Mean Variance Optimization enables us to design a portfolio from the available asset classes which will have the lowest expected variance, or market risk, at any possible expected rate of return. The line of least variance at various rates of return is called the Efficient Frontier. In his 1952 paper, Dr. Markowitz theorized that there would be a combination of variance (risk) and return in all possible diversified portfolios, and that if a risk/return graph were created that all possible portfolios would occur within an oval. In that paper he drew a graphic that looked something like the one upper chart.

Portfolios on or near the efficient frontier are referred to as “efficient” portfolios in that they are likely to create no more market variance than is necessary to achieve the desired expected rate of return. Portfolios below and to the right of the efficient frontier are considered “inefficient” because they are likely to create undue risk for the expected rate of return.

A key element to understand is the the efficient frontier has proven to be the actual limit to improving investment performance. When someone comes along with a fund or method that claims to have a greater return and/or lower long term risk putting them beyond the efficient frontier history has shown that it is unrealistic and commonly leads to large scale losses.

Using Mean Variance Optimization enables us to design a portfolio from the available asset classes which will have the lowest expected variance, or market risk, at any possible expected rate of return. The line of least variance at various rates of return is called the Efficient Frontier. In his 1952 paper, Dr. Markowitz theorized that there would be a combination of variance (risk) and return in all possible diversified portfolios, and that if a risk/return graph were created that all possible portfolios would occur within an oval. In that paper he drew a graphic that looked something like the one upper chart.

Portfolios on or near the efficient frontier are referred to as “efficient” portfolios in that they are likely to create no more market variance than is necessary to achieve the desired expected rate of return. Portfolios below and to the right of the efficient frontier are considered “inefficient” because they are likely to create undue risk for the expected rate of return.

A key element to understand is the the efficient frontier has proven to be the actual limit to improving investment performance. When someone comes along with a fund or method that claims to have a greater return and/or lower long term risk putting them beyond the efficient frontier history has shown that it is unrealistic and commonly leads to large scale losses.

The Actual Efficient Frontier

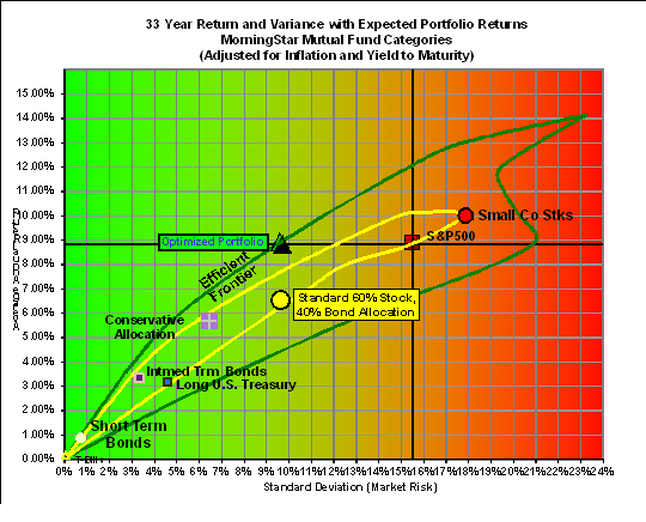

The second chart is a plot of the actual positioning of possible diversified portfolios based on market data as of August 2010. Several asset classes can be seen on both charts including the S&P 500 Stock Index, bond indexes, small cap stocks, cash or money markets, and both a standard balanced portfolio and one optimized using Mean Variance Optimization (MVO).

The yellow circle represents a portfolio composed of 60% S&P 500 Stock Index, 20% Intermediate Government Bonds, and 20% Investment Grade Intermediate Term Bonds. It is, as would be expected, located very nearly on a straight line from cash to stocks and about at the 60% point.

The black triangle is a portfolio allocation optimized using Markowitz MVO. It has the same standard deviation or market risk as the standard 60/40 balanced portfolio, but an expected return about 2% per year higher, or about the same as the S&P 500 Stock Index. It too has about 40% less risk than the Index, but potentially has the same return as the Index.

One of the most astounding things about Dr. Markowitz’s 1952 paper is that it was done long before the computing power was available to test his theory on actual market data over a long period of time. In spite of that limitation the actual plot based on decades of monthly asset class data looks amazingly like his hand sketched drawing from well over half a century ago!

Pareto’s Rule & Minimizing ExpensePareto’s Rule, sometimes referred to as “Pareto’s Law”, “the Pareto Principle”, or “the 80/20 rule” was initially developed by Vilfredo Pareto who observed in 1906 that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population and that 80% of the peas in his garden came from 20% of the pea pods. He went on to study the production of wealth in several European countries and found that the distribution was strikingly similar. It was popularized by Joseph M. Juran in his Quality Control Handbook published in 1951 and in his book Managerial Breakthrough published in 1964. In the area of management, Pareto’s Rule implies that about 80% of the results can be credited to about 20% of the managers. The Rule is sometimes summarized as “The Law of the Vital Few.”

According to Moringstar Principia’s August 31, 2010 edition, there were 2,253 distinct mutual fund portfolios that had existed for at least 15 years. The top 20% of those portfolios had an average annual rate of return of 8.92% over the previous 15 years, 2.78% better than the S&P 500 Stock Index, and over the previous 10 years had averaged 5.8%, 7.61% better than the Index. An examination of total returns reveals that the 20% were indeed responsible for 80% of the total return above that of a “no-risk” certificate of deposit or series of Treasury Bills.

In each asset class there are typically a relatively large number of managers, some of whom have both a long managerial record and exceptional returns. By finding the “critical few” and avoiding the “trivial many” we believe that we have the potential to enhance portfolio returns in a manner that should far more than offset the fees we charge for our management.

In some asset classes, such as high grade bonds, Pareto’s Rule does not seem to apply as well. The critical element in those asset classes appears to be a combination of wide diversification and low expenses. In those asset classes we gravitate toward low cost and a combination of experienced conservative management and a large asset base. We believe it prudent to avoid higher expense positions that use leveraging or relatively exotic methods.

Avoidance of Non-Systemic RiskThere are many types of risk when investing, however they can be generally classified as either “systemic” or “non-systemic.” Systemic risk is, as the name implies, the risk inherent in the system. Markets and economies rise and fall. If one is investing in a given market or a given economy then the value of investments will be affected by those fluctuations. Systemic risk can be managed, but it absolutely cannot be eliminated.

Non-systemic risk is the risk inherent in any individual security. A good example would be the stock of a large, well financed company which suddenly collapses into oblivion with little or not warning. For the casual investor investing in shares of Enron, Bear-Sterns, Lehman Brothers, General Motors, or FNMA (Fannie Mae), the reality of non-systemic risk has become apparent. To a lesser extent investors in BP discovered that no matter how well financed and profitable an individual company might be, the share value can still fall by 80% or more and the fall of that price can actually lead to financial problems for the company. Whole sectors of the market can fall with the same suddenness and degree. Prior to 2008 AAA rated collateralized mortgage obligation bonds (CMOs) were considered to be one of the safest set of investments available. In just a few months much if not most of that entire sector of the market effectively “froze” with no one willing to buy. Even when trading resumed, many issues were worth pennies on the dollar and others had no value at all.

Another example of non-systemic risk is to be found in “privately managed” accounts. In many cases those accounts are not independently audited, are commonly illiquid and often not physically and legally separated from the manager. In those cases, if the manager suffers a financial reversal, the manager’s creditors may be able to access those accounts. Bernie Madoff is an example of the worst case when using privately managed accounts. His investors received statements and regular income for years from what was revealed to actually be purely a scam.

At The Personal Wealth Coach we do not have possession of your investments nor are we in a position to access your accounts other than to manage your investments and charge those fees you have authorized in writing. We also restrict the investments we use to those registered under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (ICA of ’40) or interest bearing investments backed either by the U.S. Treasury, a U.S. government agency, or the FDIC. The Investment Company Act of 1940 requires that the actual securities be held at an independent custodian, prohibits the managers, creditors, or anyone else than the rightful owner from withdrawing funds other than for authorized fees, and requires that an independent audit be done each year by an auditor properly certified to audit such accounts. Since the enactment of the Investment Company Act no investor has lost his or her money due to any fraudulent scheme or failure of any of the associated companies. While the ICA of ’40 does not protect from market variation and down markets, it does remove the risk of misappropriation or seizure of your money by someone else.

Review and ReallocationThe last element in our methodology is founded in the deeply held belief that things change. The perfect portfolio today may be headed for trouble in just a few months. At The Personal Wealth Coach we operate on the assumption that good investments can turn bad and today’s ideal asset class may be tomorrow’s loser. We review our client’s asset allocations monthly and when any asset class approaches 10% more or less than was originally allocated we reexamine the allocation model to determine if we need to simply rebalance the portfolio or if it needs a new analysis and reallocation. We regularly review the funds we recommend and follow both their performance compared with their peers in the same asset class and the continuity of management both in the fund itself and in the parent management company. While we attempt to avoid frequent trading in order to reduce costs and, for taxable accounts, income taxation, we will not remain with a manager or management company as it deteriorates simply to avoid paying taxes on the gains.

We also make every reasonable attempt to maintain contact with our clients in order to determine if their situation has changed and as a result created a need for a different investment approach. Actual human beings are available every business day to answer the phone and speak with you on anything of a financial or investment nature.

1. Quoted from, Against the Gods, The Remarkable Story of Risk by Peter L. Bernstein, 1996, Chapter 15, page 252.

The second chart is a plot of the actual positioning of possible diversified portfolios based on market data as of August 2010. Several asset classes can be seen on both charts including the S&P 500 Stock Index, bond indexes, small cap stocks, cash or money markets, and both a standard balanced portfolio and one optimized using Mean Variance Optimization (MVO).

The yellow circle represents a portfolio composed of 60% S&P 500 Stock Index, 20% Intermediate Government Bonds, and 20% Investment Grade Intermediate Term Bonds. It is, as would be expected, located very nearly on a straight line from cash to stocks and about at the 60% point.

The black triangle is a portfolio allocation optimized using Markowitz MVO. It has the same standard deviation or market risk as the standard 60/40 balanced portfolio, but an expected return about 2% per year higher, or about the same as the S&P 500 Stock Index. It too has about 40% less risk than the Index, but potentially has the same return as the Index.

One of the most astounding things about Dr. Markowitz’s 1952 paper is that it was done long before the computing power was available to test his theory on actual market data over a long period of time. In spite of that limitation the actual plot based on decades of monthly asset class data looks amazingly like his hand sketched drawing from well over half a century ago!

Pareto’s Rule & Minimizing ExpensePareto’s Rule, sometimes referred to as “Pareto’s Law”, “the Pareto Principle”, or “the 80/20 rule” was initially developed by Vilfredo Pareto who observed in 1906 that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population and that 80% of the peas in his garden came from 20% of the pea pods. He went on to study the production of wealth in several European countries and found that the distribution was strikingly similar. It was popularized by Joseph M. Juran in his Quality Control Handbook published in 1951 and in his book Managerial Breakthrough published in 1964. In the area of management, Pareto’s Rule implies that about 80% of the results can be credited to about 20% of the managers. The Rule is sometimes summarized as “The Law of the Vital Few.”

According to Moringstar Principia’s August 31, 2010 edition, there were 2,253 distinct mutual fund portfolios that had existed for at least 15 years. The top 20% of those portfolios had an average annual rate of return of 8.92% over the previous 15 years, 2.78% better than the S&P 500 Stock Index, and over the previous 10 years had averaged 5.8%, 7.61% better than the Index. An examination of total returns reveals that the 20% were indeed responsible for 80% of the total return above that of a “no-risk” certificate of deposit or series of Treasury Bills.

In each asset class there are typically a relatively large number of managers, some of whom have both a long managerial record and exceptional returns. By finding the “critical few” and avoiding the “trivial many” we believe that we have the potential to enhance portfolio returns in a manner that should far more than offset the fees we charge for our management.

In some asset classes, such as high grade bonds, Pareto’s Rule does not seem to apply as well. The critical element in those asset classes appears to be a combination of wide diversification and low expenses. In those asset classes we gravitate toward low cost and a combination of experienced conservative management and a large asset base. We believe it prudent to avoid higher expense positions that use leveraging or relatively exotic methods.

Avoidance of Non-Systemic RiskThere are many types of risk when investing, however they can be generally classified as either “systemic” or “non-systemic.” Systemic risk is, as the name implies, the risk inherent in the system. Markets and economies rise and fall. If one is investing in a given market or a given economy then the value of investments will be affected by those fluctuations. Systemic risk can be managed, but it absolutely cannot be eliminated.

Non-systemic risk is the risk inherent in any individual security. A good example would be the stock of a large, well financed company which suddenly collapses into oblivion with little or not warning. For the casual investor investing in shares of Enron, Bear-Sterns, Lehman Brothers, General Motors, or FNMA (Fannie Mae), the reality of non-systemic risk has become apparent. To a lesser extent investors in BP discovered that no matter how well financed and profitable an individual company might be, the share value can still fall by 80% or more and the fall of that price can actually lead to financial problems for the company. Whole sectors of the market can fall with the same suddenness and degree. Prior to 2008 AAA rated collateralized mortgage obligation bonds (CMOs) were considered to be one of the safest set of investments available. In just a few months much if not most of that entire sector of the market effectively “froze” with no one willing to buy. Even when trading resumed, many issues were worth pennies on the dollar and others had no value at all.

Another example of non-systemic risk is to be found in “privately managed” accounts. In many cases those accounts are not independently audited, are commonly illiquid and often not physically and legally separated from the manager. In those cases, if the manager suffers a financial reversal, the manager’s creditors may be able to access those accounts. Bernie Madoff is an example of the worst case when using privately managed accounts. His investors received statements and regular income for years from what was revealed to actually be purely a scam.

At The Personal Wealth Coach we do not have possession of your investments nor are we in a position to access your accounts other than to manage your investments and charge those fees you have authorized in writing. We also restrict the investments we use to those registered under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (ICA of ’40) or interest bearing investments backed either by the U.S. Treasury, a U.S. government agency, or the FDIC. The Investment Company Act of 1940 requires that the actual securities be held at an independent custodian, prohibits the managers, creditors, or anyone else than the rightful owner from withdrawing funds other than for authorized fees, and requires that an independent audit be done each year by an auditor properly certified to audit such accounts. Since the enactment of the Investment Company Act no investor has lost his or her money due to any fraudulent scheme or failure of any of the associated companies. While the ICA of ’40 does not protect from market variation and down markets, it does remove the risk of misappropriation or seizure of your money by someone else.

Review and ReallocationThe last element in our methodology is founded in the deeply held belief that things change. The perfect portfolio today may be headed for trouble in just a few months. At The Personal Wealth Coach we operate on the assumption that good investments can turn bad and today’s ideal asset class may be tomorrow’s loser. We review our client’s asset allocations monthly and when any asset class approaches 10% more or less than was originally allocated we reexamine the allocation model to determine if we need to simply rebalance the portfolio or if it needs a new analysis and reallocation. We regularly review the funds we recommend and follow both their performance compared with their peers in the same asset class and the continuity of management both in the fund itself and in the parent management company. While we attempt to avoid frequent trading in order to reduce costs and, for taxable accounts, income taxation, we will not remain with a manager or management company as it deteriorates simply to avoid paying taxes on the gains.

We also make every reasonable attempt to maintain contact with our clients in order to determine if their situation has changed and as a result created a need for a different investment approach. Actual human beings are available every business day to answer the phone and speak with you on anything of a financial or investment nature.

1. Quoted from, Against the Gods, The Remarkable Story of Risk by Peter L. Bernstein, 1996, Chapter 15, page 252.